What We Owe Each Other As Music Therapists

Brea Murakami, MM, MT-BC

An update from January 18th, 2022 summarizing the impact of this blog post from July 2021 – January 2022 can be read here.

In June 2021, I published my first solo-authored journal article about the Music Therapy and Harm Model (MTHM), by which music therapists can delineate sources of harm in music therapy practice (Murakami, 2021). I’m very proud of the paper, which highlights a defining issue in clinical music therapy: how to identify and respond to harm. But, the joy of this milestone has been tainted by the actions of Michael Silverman, Lori Gooding, and Olivia Yinger. These three authors plagiarized my theoretical model in their 2020 article “It’s…Complicated: A Theoretical Model of Music-Induced Harm” after I shared an early version of my manuscript with Michael Silverman in September 2019. Essentially, their Music-Induced Harm (MIH) model reconfigures and re-labels the core components of my Music Therapy and Harm Model, but they did not cite my model even after acknowledging that they consumed and derived value in my ideas.

I first discovered they had plagiarized my work in July 2020 when I was scrolling through Twitter and discovered their Music-Induced Harm (MIH) model in a tweet from the @AmtaResearch account (AMTA, 2020a). This tweet led me on a journey through several ethical dilemmas and put me face-to-face with the failures of our professional systems and leaders that allowed Silverman, Gooding, and Yinger to evade accountability for their actions. In this paper, I outline the events I navigated to seek justice and illustrate the shortcomings I experienced. I know that my experiences are not isolated. Many other music therapists have found themselves in impossible ethical dilemmas in which they could not find resolution, and I hope that my account provides an example of systemic failure by which we might do better by each other as a professional community.

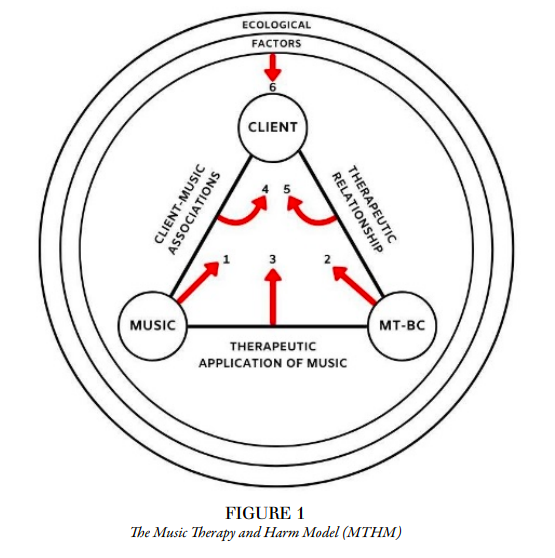

Over the past five years, I have developed the Music Therapy and Harm Model (MTHM) which outlines six potential sources from which harm can arise within a music therapy setting: 1) the music presented, 2) the music therapist, 3) the therapeutic application of music, 4) client-specific music associations, 5) the therapeutic relationship, and 6) ecological factors. A picture of my model is included below for reference.

The seeds of my model began in the spring of 2015 when I was serving on the Illinois State Task Force advocating for music therapy licensure. In 2016, I floated the idea of doing my master’s thesis on a music and harm related topic, but a mentor dissuaded me from this topic due to the lack of scholarly work in this area. At the time, the conversation around music and harm was almost nonexistent, to the point that many music therapists did not even consider that they were capable of causing or allowing harm to occur in their practice. I was still interested in the topic and went on to develop an early version of the MTHM, which I presented at the American Music Therapy Association (AMTA) conference in November 2017 with my colleague Daniel Goldschmidt. In response to our talk, we were invited by Cathy Knoll to record an episode of the AMTA Pro Podcast about my model, which was released in October 2018 (Murakami & Goldschmidt, 2018). I presented my model the following year in March 2018 at the WRAMTA conference (Murakami, 2018). After feedback from those conference presentations, I wrote and refined a manuscript I had drafted and I submitted this first iteration of the MTHM paper to the journal Music Therapy Perspectives (MTP) on July 14th, 2018. I didn’t end up publishing my manuscript at that time in order to more fully develop my model.

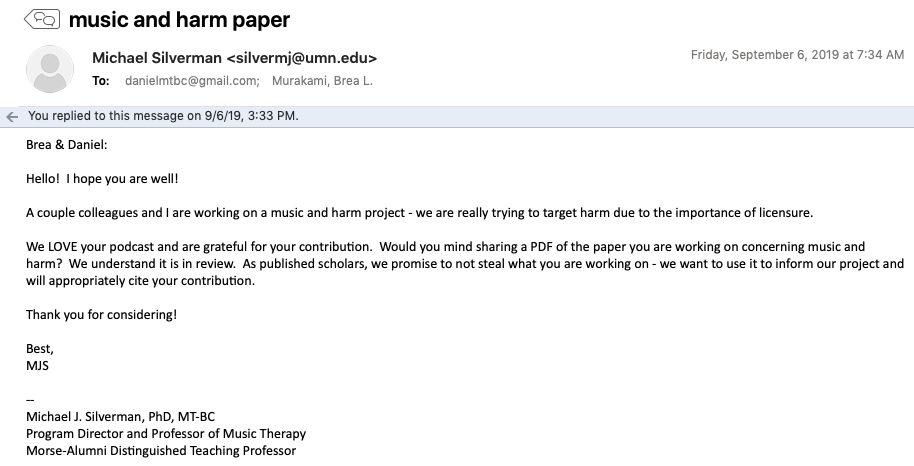

On September 6th, 2019, I received an email from Michael Silverman in which he acknowledged listening to my and Daniel Goldschmidt’s podcast about the MTHM and requested a review copy of my first MTP manuscript. In the email Silverman acknowledged listening to the podcast, saying he “LOVED” it. He specifically promised to “not steal” my work and to “appropriately cite” my contribution. A screenshot of the email is copied below:

I assumed that their project was related to state task force activities and I sent the paper draft the same day. I continued to work on the manuscript and re-submitted an updated version to the journal Music Therapy Perspectives on June 5th, 2020. A month later on July 9th, 2020, I became aware that Silverman, Gooding and Yinger (2020) published an article entitled, “It’s… Complicated: A Theoretical Model of Music-Induced Harm” in the Journal of Music Therapy (JMT) via a tweet by @AmtaResearch (AMTA, 2020a). Upon reviewing their paper, I was confused as to why my MTHM was not cited or acknowledged after the email exchange between Silverman and myself 10 months earlier. In the spirit of due diligence, I confidentially consulted with mentors and a representative of the AMTA Ethics Board before beginning the informal ethics process. On July 28th, 2020 I first contacted the authors and the JMT journal editor regarding the omission of my work. The JMT Editor reported that according to the Committee on Publication Ethics that the journal abides by, my concern was primarily an author issue and recommended that I speak with them directly.

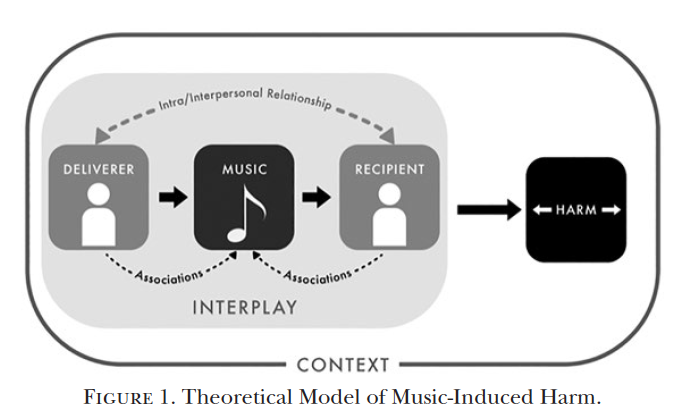

I contend that Silverman, Gooding, and Yinger plagiarized my model by not citing it as an influential factor in the development of the Music-Induced Harm (MIH) model. In doing so, they violated AMTA Code of Ethics item 3.9: “Give credit when using the ideas and works of others (AMTA, 2019).” The amount of evidence that they violated the AMTA Code of Ethics is overwhelming. The three authors failed to cite my MTHM as an influencing factor despite writing in their article, “We cultivated the MIH model using a number of existing frameworks.” Without citing my model in their article, they are unfairly taking credit as being the first, seminal framework by which scholars can conceptualize music-related harm within a unified model. Specifically, the core factors that are theorized as sources of harm within (therapeutic) music experiences are essentially the same in both models. I’ve included their diagram of the Music-Induced Harm (MIH) model below for reference (Silverman, Gooding, & Yinger, 2020).

Although the visual aspects of the MIH model and the MTHM are different at face value, the overlap between our two models is obvious. These shared factors and interactions within their MIH model and my MTHM specifically include:

- Music

- Deliverer/MT-BC

- Recipient/Client

- Intra/Interpersonal Relationship/Therapeutic Relationship

- Deliver-Music Associations/Therapeutic Application of Music

- Recipient-Music Associations/Client-Specific Music Associations

Their MIH model also includes an Interplay factor that aligns with the Ecological Factors of my final MTHM, but I don’t attribute these similarities to plagiarism because the manuscript I shared with Silverman didn’t include the Ecological Factors. I acknowledge that the intended scope between these two models is slightly different. That being said, their model inherently holds a clinical focus that cannot be ignored. All three authors are board-certified music therapists and they cite an overwhelming amount of clinical music therapy research as the foundation of their model.

Additionally, Silverman, Gooding, and Yinger practiced discrimination against my scholarship by not citing the 2018 AMTA Pro Podcast that clearly influenced their thinking. If the initial version of my model had been published in MTP in 2018, then it is more likely that they would have cited my work. I believe that their lack of citation is due to unfair bias against grey literature, without thoughtful consideration of the merit of my ideas. Grey literature is defined as material that is produced “on all levels of government, academics, business, and industry in print and electronic formats, but which is not controlled by commercial publishers” (Grey Literature Report, n.d.).

The three authors continue to ignore other factors that prevent them from acknowledging the seriousness of their actions. Previous to this year, I had looked up to the three authors as leaders in the music therapy community, but now many of their actions feel corrupt. For example, all three authors serve as associate editors for the journal in which they published their paper. Reading the “Positionality and Privileges” section in the paper they plagiarized me in is especially ironic. In this section, the authors explicitly “recognize [their] privileges, experiences, and voices related to the development of the [MIH] model.” Additionally, they refuse to acknowledge that cryptomnesia (i.e., inadvertent plagiarism) might explain their beliefs (Gingerich & Sullivan, 2013), despite Silverman clearly stating that he (at least) consumed and found merit in my ideas via the AMTA Pro Podcast. To add to my confusion, Silverman has since cited my work in his 2021 presentation at the GLR/MWR Virtual conference, but has ignored my requests to amend the original JMT article to cite the AMTA Pro Podcast.

The three authors’ plagiarism is a serious transgression that should disappoint all music therapists. The science and practice of music therapy benefits when good ideas are readily available for everyone to consider, implement, and provide feedback on as a community. We learn from others in the music therapy field via an open flow of information. When doing so, we need to keep an accurate throughline of where ideas originated. Failure to appropriately cite authors disregards the effort and merit of original ideas that move knowledge forward. I feel strongly that my model helps music therapists articulate their value to decision-makers in advocacy efforts that had initially spurred my interest in this topic. As such, I initially disseminated my MTHM via less formal conference presentations and podcasts in favor of more immediate application. Although I openly communicated my ideas, I believed that members of my community would reciprocate my efforts by citing my work.

Silverman, Gooding, and Yinger’s failure to cite my ideas has had several repercussions on my career. First, the actual timeline by which the topic of harm unfolded in the music therapy field has been obscured in the peer-reviewed literature. By declining to cite my work, Silverman, Gooding, and Yinger took advantage of my status as an early-career academic and my generosity in order to elevate themselves. Furthermore, I was left with no options when trying to publish my MTHM article in the well-established journal, Music Therapy Perspectives (MTP). After my manuscript had been approved by three peer reviewers, I was given no good choice but to withdraw my manuscript at the last stage before publication when the MTP editors insisted that I cite Silverman, Gooding, and Yinger. The editors maintained their position on this point despite agreeing that my submission’s timestamps preceded Silverman et al.’s publication. It was impossible for their paper to have influenced my own. Instead, the MTP editors insisted that I cite the authors, my plagiarizers, on a technicality because their paper had been published before mine, even after I shared the chronology of the situation up to that point. As a result, the publication date of my paper was pushed back by several months as I searched for an alternative peer-reviewed journal to publish in, further obscuring the actual timeline of this topic.

I have brought my concerns directly to the authors several times, but they have consistently denied that my model had any influence on their MIH model. My first attempt at informal resolution occurred on August 5th, 2020 when I had a 45 minute Zoom conversation with Michael Silverman in which he categorically denied several times that my model influenced their thinking. When I asked for evidence that their MIH model existed before emailing me in September 2019, he screen-shared and showed me hand-drawn versions of their model’s evolution saved to Google Drive. However, these pictures were titled with dates that were two weeks after he had emailed me on September 6th, 2019. After filing a formal ethics grievance against Silverman, Gooding, and Yinger with the AMTA Ethics Board on September 3rd, 2020, Carol Shultis, the co-chair of the ethics board who was handling this case, sent me a summary of their formal response to my grievance which stated:

“While we reviewed a number of additional papers during the conceptualization and writing of our article, these papers were not included as citations or references because they did not influence our thinking or concepts. For example, we read and critically appraised Marik and Stegemann (2016), Watt-Jones (2010), Lozon and Bensimon (2014), and Brown, et al. (2016), among others. While we read and critically appraised these studies, we did not cite these studies as they did not impact our thinking, concepts, or work. This was also the case for Brea Murakami’s concepts. Moreover, this is common practice in scholarly work: Authors typically review a great deal of literature but not all that literature impacts their work and requires a citation.”

I tried to schedule an informal mediation meeting with the three authors with Shultis serving as a mediator. Unfortunately, the meeting never occurred because of formal and informal barriers that eroded my trust in the Ethics Board policies and Shultis’ management. Formally, several informal mediation processes as Shultis explained them suppressed my ability to advocate for myself. For example, Shultis initially explained that while I was allowed to have a representative at the mediation meeting, that they could not speak on my behalf. Instead, she explained that they could be on the call for me to consult with during breaks from the mediation meeting. She only relented after my representative had an extended conversation with her about why representatives exist. Additionally, all parties would have been required to agree to a non-disclosure agreement, by which I could not access, use, or disclose specific details of the mediated conversation in perpetuity, theoretically barring me from seeking external mediation or legal counsel.

Furthermore, Shultis’ actions undermined the integrity of her role as a co-chair of the ethics board, leading me to become disillusioned with the ethics grievance process. Several times Shultis shared condescending opinions that led me to distrust her neutrality regarding my grievance. For example, when I voiced concern that Silverman et al.’s article featured a sentence similar to my own writing, she commented that I should take it as a compliment that my writing was as good as more established scholars. In another conversation, she commented that she didn’t see the conceptual similarities between our two models, elaborating that my model would be better applied to clinical music therapy classes, while theirs would be better taught in psychology of music classes. Most troubling was Shultis’ failure to ever acknowledge Gooding’s glaring conflict of interest in her dual roles as President Elect and respondent to my grievance. In her role as President Elect of the American Music Therapy Association (AMTA Bylaws Article IV, Section 7; AMTA, 2020b), Gooding is the communication liaison between the Board of Directors and the Ethics Board. Either Shultis was unaware of Gooding’s conflict of interest due to her own lack of knowledge about the AMTA Bylaws regarding her board, a glaring oversight in itself, or Shultis obscured Gooding’s dual roles.

Furthermore, Shultis’ responses to our communications were often staggered by several weeks or months and I often had to initiate communication to get updates. All being said, my formal contact with the ethics board spanned nine months from filing my formal ethics grievance in September 2020 to withdrawing my grievance in June 2021. No progress had been made toward any resolution. I finally decided to abandon the AMTA ethics grievance process as a dead end. As a final step, in June 2021 I emailed the three authors individually with my previously-prepared mediation statement to no response. Additionally, I’ve shared my perspective of my ethics experience with Shultis directly, with no response from her.

The past year of navigating this ethical dilemma has been emotional for me. I’ve felt gaslit and personally doubted the ethical foundation of the music therapy profession that I’ve been a part of for half of my life. I’ve come to terms that it was never possible for me to gain formal resolution through the ethics process as it is currently set up. It was difficult for me to pursue meaningful accountability when I was repeatedly treated as a legal liability as a grievant. The most frustrating part of this journey is knowing that I had every advantage to fully pursue justice. I do not fear direct retaliation from the authors, this situation does not impact my livelihood, and I have documented proof of my grievance. I have no dependents to care for and have been able to give my full attention and patience as I waded through the “proper” channels. And still, I could not find resolution and I have strong doubts anyone could.

I cannot imagine how many other music therapists have not had the same opportunities to pursue accountability. Anecdotally, I know that I’m not the only music therapist who has been wronged by another professional and let down by the AMTA ethics grievance process. Although I am deeply invested in music therapy, our professional field has been unhealthy for a while now. I have heard first- and second-hand accounts of “horror stories” about poor educational programs, internships, and working conditions that have left many music therapists burnt out or cynical. These circumstances make music therapists less available to our clients, both emotionally via burnout or literally when clinicians leave the workforce. I know how impossible taking the next step forward can feel when systems are working against your best interest, rather than supporting progress. But, we cannot sit by doing nothing.

Moving forward, it’s clear that we need to reform how interprofessional ethics are handled. My only ask is that we as a group reflect on how this situation might have gone differently and how we as an organization can do better. If you have had experiences that resonate with mine, I encourage you to not become bitter with the systems and people that have failed us. After the frustrations of the past year, I understand even more deeply the responsibilities I have to my students and colleagues as one of many pillars of our community. Pillars support and elevate a building, stabilizing it through earthquakes and storms. Similarly, the pillars of the music therapy profession are supposed to take on heavy and important responsibilities with thoughtfulness, competence, and integrity. It’s demoralizing that Silverman, Gooding, and Yinger didn’t fulfill their obligations to me as a fellow member of the scientific community and that Shultis was not able to provide the procedural support I was seeking. But through their actions, I’ve better learned how not to act when others bring challenging information to me.

As leaders, we are the first guard for making sure we are staying accountable to the community values we are acting in service of. If someone has the courage to challenge me in the spirit of those shared values, I try my best to listen and be thoughtful. I should always consider that the person I’m talking to is trying to make things a little better. As music therapists, we are all pillars of our community, whether it’s supporting our clients, our colleagues, or our students. Looking upward, re-centering our shared values and acting with intentionality is the only path I can see forward.

An update from January 18th, 2022 summarizing the impact of this blog post from July 2021 – January 2022 can be read here.

References

- American Music Therapy Association (2019). American Music Therapy Association code of ethics. https://www.musictherapy.org/about/ethics/

- American Music Therapy Association [@AmtaResearch]. [2020a, July 9]. These music therapy researchers developed a theoretical model for music-induced harm (MIH). Learn more about the factors informing MIH and how to protect against them: https://is.gd/GXw5T9 #mtresearch #musictherapy @AMTAInc @OUPAcademic [Image attached] [Tweet]. Twitter.

- American Music Therapy Association. (2020b, November 21). American Music Therapy Association bylaws. https://www.musictherapy.org/members/bylaws/

- Gingerich, A. C., & Sullivan, M. C. (2013). Claiming hidden memories as one’s own: A review of inadvertent plagiarism. Journal of Cognitive Psychology, 25(8), 913-916. https://doi.org/10.1080/20445911.2013.841674

- Grey Literature Report (n.d.). What is grey literature? https://www.greylit.org/about

- Murakami, B., & Goldschmidt, D. (2017, November 16-19). Music and harm: What we know and what we need to know. [Conference presentation]. AMTA 2017 Conference, St. Louis, MO, United States.

- Murakami, B. (2018, March 1-3). A framework for understanding the potential for harm within music therapy. [Conference presentation]. WRAMTA 2018 Conference, Ontario, CA, United States.

- Murakami, B., & Goldschmidt, D. (Hosts). (2018, October). Potential harm in music therapy? [Audio podcast]. https://amtapro.musictherapy.org/?p=2100

- Murakami, B. (2021). The Music Therapy and Harm Model (MTHM): Conceptualizing harm within music therapy practice. ECOS, 6(1), 003-003. https://doi.org/10.24215/27186199e003

- Silverman, M.J., Gooding, L. F., & Yinger, O. (2020). It’s…complicated: A theoretical model of music-induced harm. Journal of Music Therapy, 57(3), 251-281. https://doi.org/10.1093/jmt/thaa008